How do we process new information?

The Sun and the Earth do not always conform to our expectations

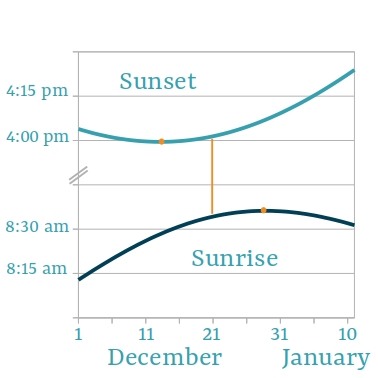

Sometime in December 2021 I saw a graph representing the times of sunrise and sunset in Brighton for the last weeks of the year. I was delighted by how clearly it showed the sun rising a bit later each day for a while even after the winter solstice (which I blogged about here). So I went on to retrieve the data for Hamburg and made my own graph based on that. Around here the earliest sunset was also on the 13th of December and the latest sunrise was today on the 29th of December. Were you aware of this fact? I spoke to some people about this, mainly in the context of me having them calculate the maximum and minimum values as well as the smallest difference between the two functions and they were quite surprised. Most of us know that for the nothern latitudes the winter solstice takes place on the 21st or 22nd of December each year which also marks the time of the shortest night. It might seem plausible that this should coincide with both the earliest sunset and the latest sunrise.

The reasons behind this rather more complicated scenario? The geometrical arrangement of the Sun, the Earth, the tilt of the Earth’s rotational axis, the shape of its orbit and the lack of consistency in velocity. Another factor is our personal position in relation to the equator. Our mechanical watches function based on the assumption that each day (i.e. the time it takes for the Sun to appear at its maximum altitude in the sky twice in a row) takes 24 hours. On the other hand, sundials measure the true length of a day. It varies through the year by about plus or minus 15 minutes. Another consequence of the astronomical realities is the so called analemma: If we take a picture of the sky at the same local time for a year and then superimpose them, the resulting image will show a tilted figure eight with the angle again depending on our latitude. If the Earth’s orbit was a perfect circle and its rotational axis was upright, the sun would appear at the same position each day. The more I ponder this, the more tricky the image that forms in my brain. But also the more fascinating. Maybe it feels the same to you. Or maybe nothing about this is news to you.

How do we process new facts?

Whenever some new piece of reality comes our way after we had been convinced we knew all about the subject, it can have interesting effects on us. Time for another quote by Ragunath Cappo and his former band “Shelter”:

Things we knew for sure

Sometimes we need to correct themWe’ve got to rearrange our thinking

Or we’re just like flies on glassRearrange our thinking

Shelter, “Revealed in Reflection”

Or we’re never gonna last

There is not much progress in keeping thoughts that we had assumed to be true but which turned out to not be correct after all. Yet a lot of debate these days is about assumed and real truths, discussions consuming large amounts of energy and emotional investment. Incorrect assumptions find their ways into our memories by frequent repetition. At least in Germany a word search of the news shows how the term “Omnikron” has managed to imprint itself on some brains.

Some questions will be helpful here: Is the subject at hand about something that can relatively easily and reliably be measured as in the astronomical example above. Is it about more complex issues that are still based on natural phenomena like climate, enovironmental or nutrition sciences? Maybe about psychological contexts like the description of human behaviour? Or does it deal with human conventions like orthography that is sometimes subject to official changes? Is my truth an opinion, an assumption or a factual claim? Could there be negative consequences of me maintaining my truth? Would they be negligible or substantial? Or would the (seeming) contradiction be basically inconsequential? What is the source of my information? How do I know how to judge the reliability of such a source? Clearing all this up for myself will reduce the potential of conflict during the discourse for me. Ideally, this should be done by as many of us as possible.

How do we react to our truth being confronted with reality?

Human history is full of examples of more or less successful adaptation to new bits of knowledge. One very human way to deal with contraditions is the so called confirmation bias. We are more aware of and more easily accept new information that confirms our worldview. This behaviour may appear irrational but served as an evolutionary advantage in our early history: Sharing an opinion with your tribe helped avoid being outcast and made your individual survival more likely. Also it feels safer and is thus more economical to our brains to maintain our world views instead of constantly deconstructing them every time someone tells us something unexpected. The seeming lack of rationality does make some kind of sense after all. On the other hand this process leads to accumulation of a certain portion of “knowledge” that defies reality.

On the other end of the spectrum, over time humanity developed the scientific method. This includes asking questions, developing hypotheses and subsequently testing them in experiments. Hypotheses are afterwards accepted or rejected based on the objective results, ideally not depending on the worldview of the experimenter. The fact that we as humans can on the one hand be highly irrational and on the other hand come up with this type of process is astounding to me.

Currently we can observe how different people experience and interpret this cycle of hypothesising, accepting, rejecting and in some cases reassessment of data. Especially when media, politicians and scientists do not communicate a somewhat uniform picture, to put it politely. Possible reactions range from “Isn’t it great how realiably and quickly research keeps us updated all the time?” to “Why do they contradict themselves every few weeks? How can I trust them?”

What can we do with all this?

The most sensible approach to confirmation bias is to be aware that we ourselves also are under its influence and for good reason. In the end this all is about our need for security. Simple absolute answers to complex question tend to be more welcome, as is sticking to a message once it has been presented. Cautiously vague statements or a change in direction based on new data can be seen as signs of insecurity. In times of crisis such as this one, science and politics as well as media have to bridge the gap between scientific accuracy, communicabilty, simplification and in the case of politics their ability to act. Our responsibilty as citizens is to be as aware of these facts as clearly and as often as possible, to show empathy with other people’s confirmation bias as well as our own and at the same time do our bit to keep our truth as close to reality as we can. And then to politely and solidly offer those around us opportunities for them to rearrange their thinking if needed.

What do you think?

What about you, how do you feel about your truth being challenged with new information? How easily can you adapt your worldview? What could possibly make this updating process into a pleasant experience for you? And when is the earliest sunrise going to be?

Leave a Reply